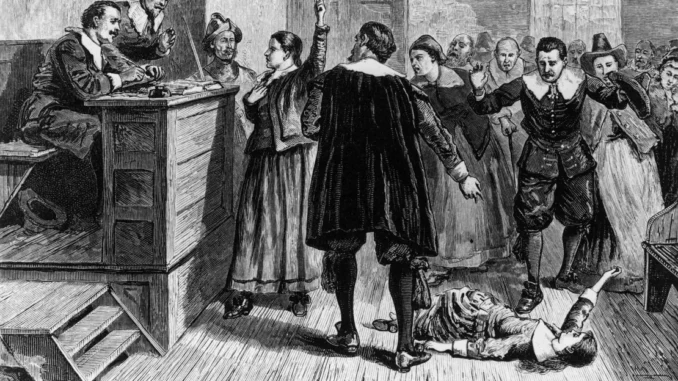

Up to 60,000 so-called “witches” are thought to have been executed across Europe during the 1600s and 1700s, with tens of thousands more put on trial.

But new research suggests that one English woman convicted of witchcraft and condemned to be hanged may have escaped the noose.

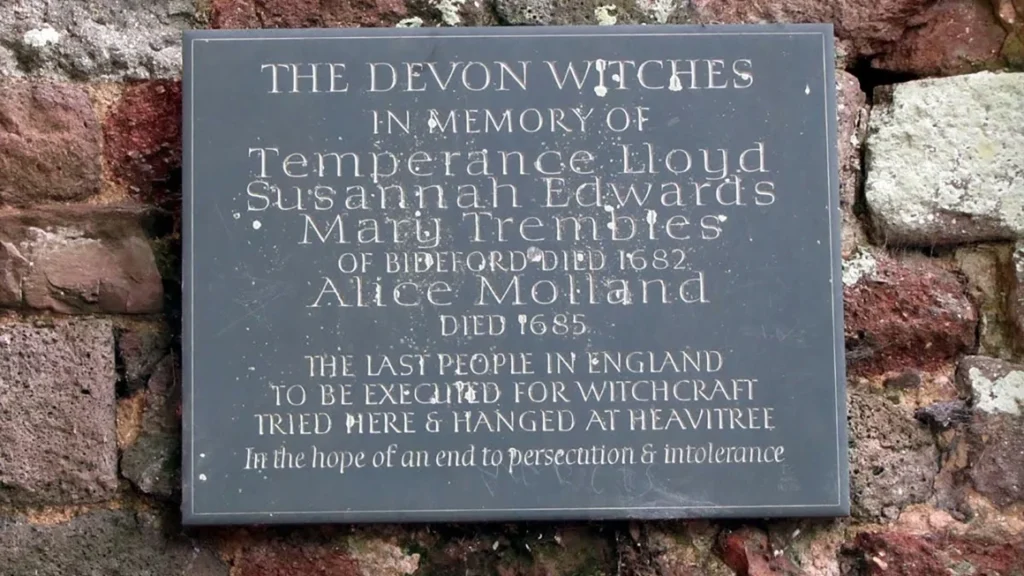

Alice Molland – who has long held the tragic record of being the last woman in England to be hanged as a “witch” – was sentenced to death in 1685. Over three centuries later, in 1996, a plaque was installed to commemorate her execution at the site of her conviction, Exeter Castle in Devon, southwest England.

But after a decade-long hunt through the archives, Mark Stoyle, professor of early modern history at the UK’s University of Southampton, believes that “Alice Molland” was actually Avis Molland – and died a free woman in 1693, eight years after her supposed execution.

If his theory is correct, it means that England stopped executing so-called “witches” three years earlier than previously thought. The last to suffer the fate would become the “Bideford three”: Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles and Susannah Edwards, also from Devon, who were hanged in 1682.

Molland was sentenced to the gallows for “witchcraft on the bodyes of Joane Snell, Wilmott Snell and Agnes Furze” in March 1685, according to court records.

She has long remained a mystery to historians, her only trace her death sentence: annotated with a wheel symbol and the word “susp[enditur]”, condemning her to the gallows. Her conviction was unearthed in 1891.

But Stoyle believes that a court clerk could have misheard the defendant’s name. In 2013 he found a reference to Avis Molland – an unusual surname in Exeter – which suggested she was in jail just three months after “Alice” had been sentenced. By combing through city records, he has reconstructed much of Avis’ life.

Part of Exeter’s “underclass,” in Stoyle’s words, a younger Molland – who was born Avis Macey – had already fallen foul of the law. In 1667, she and her roofer husband were charged with enticing a child to steal tobacco. The case was eventually dropped. She had three daughters, all of whom died in infancy.

In June 1685, Avis Molland – by now widowed – emerges in court records as an informant about a potential revolt, at a time when the Duke of Monmouth was attempting a rebellion against the king. She appears to have testified about a seditious inmate in Exeter jail – suggesting that she, too, was incarcerated, three months after “Alice’s” trial.

As the jail filled with rebels, Stoyle believes that Avis may have been reprieved. Avis Molland died a free woman eight years later. She was buried in St. David’s church cemetery, near today’s railway station.

Although he cannot prove Avis was Alice, Stoyle says that Molland, whom he calls a “historiographical will’o the wisp”, was a prime candidate to be accused of witchcraft: poor, ageing, female and single. “They were overwhelmingly poorer women with no one to protect them,” he told CNN. “Sometimes they were more outspoken or quarreled with neighbors.”

Innocent women who looked the part

At least 500 “witches” are thought to have been executed in England between 1542 and 1735, when witchcraft was a capital offense, according to government figures, although historians think the real number could be double. Scotland killed around 2500 “witches”; across Europe it is believed that up to 60,000 were executed. The trials swept to North America as well – where, most famously, 19 were executed in Salem, Massachusetts, with more dying under torture and investigation.

The vast majority were innocent women who simply fitted the bill – usually older, single and often using walking aids. “It was anti-women, anti-ageing and anti-disability,” said Stoyle, who added that the laws were originally created out of paranoia that Catholics might use witchcraft to kill Henry VIII and Elizabeth I. “It’s ironic that a law brought in primarily against Catholic priests was turned against ordinary women in the provinces,” he said.

“These people should have been exonerated in 1735,” said Charlotte Meredith, whose campaign, Justice for Witches, is lobbying for English victims to receive posthumous pardons as a “formal acknowledgement of the gross miscarriage of justice.”

John Worland, a retired police inspector from Essex, in southeast England, said that “we shouldn’t forget” the women’s stories.

Since 1996 a plaque has honored Molland at Exeter Castle, where she was condemned to death.

Essex executed 82 people for witchcraft – more than any other county in England. Worland has spent 18 years unearthing victims’ details, and has successfully campaigned to have memorials to executed “witches” in Colchester and Chelmsford.

“It was almost always based on neighbouly disputes,” he said of the women. “They were misrepresented throughout history.”

Stoyle will publish his findings in November’s issue of the UK’s Historical Association’s magazine, “The Historian.”

“Even if I’m completely wrong, the work has brought Avis Molland’s story to light,” he said. “She was a very humble woman who’d never have been commemorated in any way.”

One person who’s less convinced is Judy Molland, who grew up as the daughter of a prebend of Exeter Cathedral, and was instrumental in erecting the privately funded plaque to the four Devon women in 1996.

Molland, who learned about “Alice” in the 1970s and “outraged” her father at the suggestion they might be connected, spent two summers researching her in the 1990s.

“I found fascinating stuff but never her name,” she said. She has written a novel imagining Alice’s life.

“I’m completely convinced there was an Alice,” she said of Stoyle’s discovery.

“And if it wasn’t Alice, it would be some other woman accused of witchcraft. That’s the point.”